The Brother Brothers

The Brother Brothers are Adam and David Moss, identical twins carrying on the folk tradition for a new generation. Using minimal instrumentation, heartfelt lyricism, and harmonies so natural they seem to blend into one beautiful voice, the siblings draw on the energy and creativity of Brooklyn, New York for their full-length debut album, Some People I Know.

The Brother Brothers’ acoustic project emerges from several years spent traveling the country, both separately and together, playing in varying ensembles and sometimes settling in separate cities. Though each writes his fair share of the discography independently, the brothers’ palpable fraternal bond produces a togetherness in these songs that few bands can offer.

The title, Some People I Know, refers to the resonating personal nature of these songs. As David explains, “I think every song on the album is about a person or a character, and in a way, is a reflection of ourselves.” Track after track, this sentiment rings true; “Mary Anne” is an encouraging ode to a friend with depression. “Banjo Song” conveys a conversation with someone who gives up playing an instrument after a hurtful breakup. “The Gambler” honors an old man who makes his living at Atlantic City casinos.

The duo masterfully captures familiarity in human experiences, their nomadic background making that no surprise. “Adam and I are definitely the kind of people that have trouble staying in,” says David. “We love surrounding ourselves with people that make us feel good, and grow. That’s part of the beauty of living in New York and living in Austin and Boston and traveling the country – wherever you go, you’ve got friends and people that really shine and help you shine a little brighter.”

David has bartended in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn for six years, seeing firsthand his regular customers and friends being priced out of the area. The disheartening change inspired “Frankie,” a song in which a close-knit community slowly shrinks, as a result of growing greed outside its control. The song’s powerful chorus makes a memorable statement true to folk tradition.

Although young men, The Brother Brothers have boasted this sterling folk sound for decades. Growing up in Peoria, Illinois, they sang along as children to their father’s record collection of the Kingston Trio, the Everly Brothers, the Beatles, and the Beach Boys. “That’s where we learned to sing harmony and then one thing leads to another,” says Adam. “All of a sudden we could harmonize to anything we wanted to. It was a very natural progression.”

After earning music degrees at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, the brothers set off on separate musical journeys. Adam traded in the viola for a fiddle and joined Green Mountain Grass, Austin’s premier gonzograss band. David spent a short stint in Chicago, then moved to Austin and formed a progressive folk group called The Blue Hit.

Once in Austin, David discovered the music of Texas songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Blaze Foley and began writing songs shortly thereafter. In 2011, he entered (and won) the Newfolk songwriting competition at Kerrville Folk Festival. “Going to the folk festival each year has been a constant source of new friends and some of the purest inspiration we’ve ever known,” says Adam, who went on to talk about the value of artists as friends and the creative influence they can have on you.

From Austin, Adam moved to Boston, where he busked in the subway in order to hone his talent as a fiddler. After a couple of years, the twins reunited in Brooklyn, where The Brother Brothers project was finally born. Before long, they accepted invitations to open tours with Sarah Jarosz and Lake Street Dive. They released an independent EP, Tugboats, in 2017, followed by a national tour with I’m With Her in 2018.

Speaking about their live shows, Adam says, “I feel like there’s definitely like a living room vibe. Most of our experience before we were performing as a duo was, you know, sitting around song circles with friends, playing and creating a very homey, small-room environment.”

That sense of familiarity has served the siblings well on Some People I Know. After going on tour with Anaïs Mitchell’s stage production of Hadestown, David wrote “Colorado” to pay homage to friendships made on the road, brief as they may have been. Adam wrote the lively fiddle tune “In the Nighttime” in order to attract passersby in the Boston subway. By using a different microphone set-up, the track stands out on Some People I Know – and not just because of the yodeling.

As the record returns to a gentle pace, “Red and Gold” harkens back to Simon & Garfunkel, while “Ocean’s Daughter” (written with Rosie Tucker) meshes the duo’s sound with klezmer music. The portrayal of a doomed relationship in Peter Rowan’s “Paper Bride” is perhaps the album’s most cinematic moment. Quietly closing the album, Buck Meek’s “Sam Bridges” is a beautifully told tale of the vagabond, and “Goodbye Old Silver,” is poetic gratitude paid to seasons’ change.

The Brother Brothers recorded Some People I Know at Mark Ettinger’s Lethe Lounge in New York City with producer Robin Macmillan and engineer Jefferson Hamer. While the songs capably capture a modern snapshot of their surroundings, the album itself retains a timeless feel – something the brothers intentionally accomplished. “I just want people to listen to it once and want to listen to it again,” David says of the album. “And every time they listen to it, I want them to find something new and in some way relate it to themselves. Whether they’re listening to it today or in 40 years, I hope it will make them feel just the same.”

Dead Horses

At fifteen, Dead Horses frontwoman Sarah Vos’ world turned upside down. Raised in a strict, fundamentalist home, Vos lost everything when she and her family were expelled from the rural Wisconsin church where her father had long served as pastor.

“My older brother was diagnosed with schizophrenia and my twin had mental illnesses and cognitive disabilities,” explains Vos. “When the church kicked us out, they basically told my dad, ‘If you can’t lead your family, how can you lead your church?’”

What happened next is the story of Dead Horses’ stunning new album, ‘My Mother the Moon,’ a record full of trauma and triumph, despair and hope, pain and resilience. Blending elements of traditional roots with modern indie folk, the songs are both familiar and unexpected, unflinchingly honest in their portrayal of modern American life, yet optimistic in their unshakable faith in brighter days to come. Earthy and organic, Dead Horses’ songs often reveal themselves to be exercises in empathy and outreach; not only to find meaning in the struggles Vos endured, but also to embrace kindred souls on their own personal journeys of self-discovery.

“At the time we were expelled, we lived in the church’s parish house,” explains Vos. “Suddenly, my father was unemployed and my family was homeless. My parents couldn’t afford insurance for the medical care my siblings needed. We were kicked out and completely abandoned.”

However, Vos’ love of music carried on after she left the church.

“Almost half of those services [were] just singing hymns,” she reflected in a recent interview. “I also went to a parochial school, so I had to memorize hymns and Bible verses all day, too. When I really look back, before I had the chance to explore music on my own, that was really central. Even the way I write songs [today] is reminiscent of hymns. That’s maybe why I was so drawn to folk music to begin with: it’s geared towards communities singing it together.”

By the time Vos turned 18, her family had begun to get back on their feet. She headed to Milwaukee for college, and there, came to terms with revelations about her sexuality that her religious upbringing had forced her to repress. The mix of freedom and relief and shame and guilt was overwhelming, and a depressive breakdown ensued.

“I couldn’t take care of myself,” she remembers. “I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t do anything. I stopped going to classes, and then I dropped out altogether and moved back home to Oshkosh. That’s where I met Dan.”

When bassist Daniel Wolff and Vos first started playing music together, it felt as if the clouds had finally parted. Vos introduced songs she’d been writing since high school open mics, Wolff learned a new instrument for the band (the double bass), and within months, they had earned a devoted local following. Regular gigs led to steady residencies led to regional touring and their first recordings. Two of the band’s original members ultimately left the group due to opioid addictions (“I still see the pawn shop sticker every time I look at my guitar tuner,” remembers Vos), but the Dead Horses moniker the pair created as a tribute to a friend who’d over-dosed from heroin stuck even after their departure.

When it came time to record ‘My Mother the Moon,’ Vos and Wolff traded Wisconsin for Nashville to collaborate once again with producer/drummer Ken Coomer (Wilco, Uncle Tupelo). Cut primarily live in the studio over the course of two weeks, the album is raw and understated, drawing its potency from the power intimacy and hushed revelation. With a sound that calls to mind everything from Joni Mitchell to Gillian Welch, Vos draws on a Biblical lexicon in her lyrics, but the gospel of Dead Horses belongs to no particular religion. Instead, these are songs of the people, stories of Vos’ own efforts to come to terms with her turbulent upbringing as well as stories of the men and women she grew up with in a rural America.

“As much as I want to express the narrative of my own life within the lyrics, this album is also naturally very reflective of what I’m observing every day on the road,” Vos explains. “One of the hardest things in life is watching your family suffer, to be so close but unable to ease their pain. Visiting my siblings in psych wards hurt me in a way that I’m still not sure I’ve made sense of. While I can look back now and say that it maybe wasn’t conducive to me developing in a healthy way as a young person, I can see that it instilled such a sense of empathy in me. As much as that can feel like a weakness sometimes, I think it’s also a great gift. An essential part of any Dead Horses song or show is that sense of compassion for strangers.”

On the gently fingerpicked “Swinger in the Trees,” Vos uses a Robert Frost poem as a jumping off point to explore the ways in which we isolate ourselves, while the waltzing “My Many Days” reckons with how we find fulfillment with our limited time on this Earth, and the tender “Darling Dear” comes to terms with the fact that our closest loved ones will always, in some ways, remain a mystery to us. Even when Vos approaches the political, as she does on “Modern Man” and “American Poor,” she does so on a very personal scale.

“Poverty doesn’t discriminate,” she reflects. “If you’re poor, you’re poor, but there are a lot of ways to be poor. You can be poor in spirit or poor in knowledge. Ignorance is one of the deepest kinds of poverty.”

Perhaps the album’s most arresting moment arrives with closer “Ain’t No Difference,” a heartbreaking, elegantly orchestrated track that swings manically between major and minor keys. Inspired by a vivid memory of a night of bitter conflict in her childhood home, Vos sings, “The house is gone now / It’s an empty lot now / There ain’t no difference.”

Far from obliterating the past, though, ‘My Mother the Moon’ draws strength from it. It’s an album of catharsis and redemption that comes at a time when both are in high demand and short supply.

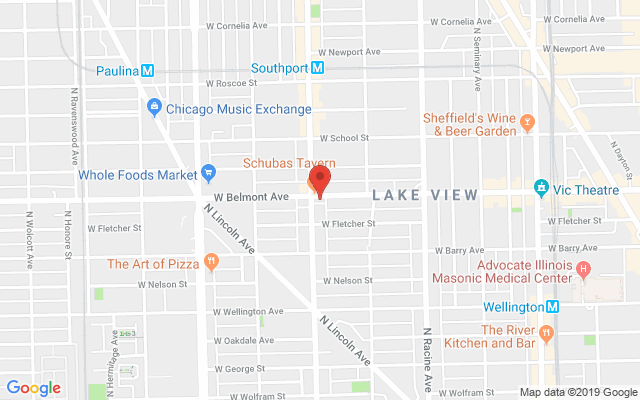

This show is at Schubas

Schubas

3159 N Southport Ave

Chicago, IL 60657

(773) 525-2508